Pandemic politics

Omicron – between panic and complacency

It will be some time before we know much about the Omicron variant – its infectiousness, its virulence, its reaction to vaccines and treatments and whether it will displace Delta. Until then there will be no shortage of anecdote and speculation, however. The absence of such evidence has not held Morrison back from stating categorically that there will be no more lockdowns.

Writing in The Conversation Ed Feil of the University of Bath, England, provides a cautiously-worded situation report as at November 29: Omicron: why the WHO designated it a variant of concern. A WHO report written in October, before the Omicron variant emerged, outlines the vaccination situation in Africa and the difficulty in securing COVAX supplies. That report reminds us that Africa has fully vaccinated only 77 million people, 6 percent of its population. On the ABC’s Breakfast program on Monday Angelique Coetzee, head of the South African Medical Association, reminded us of the consequences of the world ignoring Africa, stating that “No one is safe until Africa has been vaccinated”. This call has been repeated by President Biden in a statement on the Omicron variant, in which he calls for more rich countries to contribute to global vaccination, and for a waiver of intellectual property regimes on Covid vaccines so that they can be manufactured globally. Melissa Sweet, writing in Croakey – Two years later, and Omicron is a reminder of how little we’ve learnt – reinforces WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus’s calls for a concerted campaign to vaccinate people in low-income countries, and notes that the Omicron variant possibly emerged in Europe rather than in Africa.

The best sources for frequently-updated information are probably Norman Swan’s Coronacast, the WHO weekly epidemiological updates for those with an appetite for analysis, and Our World in Data vaccination data by country.

The Omicron variant reminds us once again of the Commonwealth’s administrative ineptitude. It was in December 2019 that news of Covid-19 emerged. We had forgotten the lessons from the 1918 flu pandemic, and by the 1990s, in spite of its constitutional responsibility for quarantine, the Commonwealth had closed its remaining quarantine stations. In the two years since the world learned about Covid-19 the Commonwealth could have constructed specialised quarantine facilities, but we are still fiddling with state-by-state arrangements for hotel quarantine. And in response to Omicron we are still dealing with the half-hearted approach, adopted by the Commonwealth and New South Wales governments, that tries to manage the pandemic by some compromise between an imagined trade-off between health and economic objectives, while failing on both fronts.

By the way, if you’re wondering why the WHO seem to have skipped over so many letters of the Greek alphabet, going from Delta to Omicron, the New York Times has a neat explanation.

Coronavirus in Australia

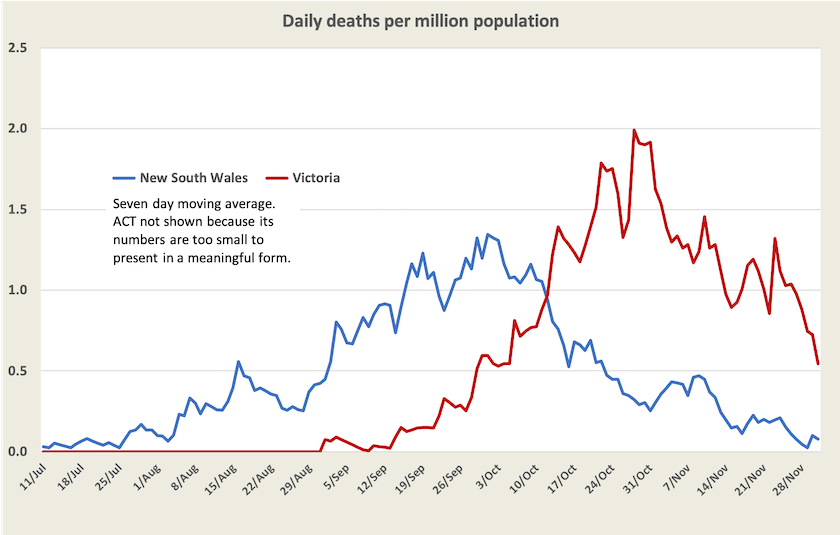

In the three states and territories – New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT – where Coronavirus is circulating, deaths and hospitalizations has been brought down from earlier high points. The graphs below, derived from the Fairfacts Data website, shows the number of daily deaths and the number of people in hospital with Covid-19, per million people in those jurisdictions.

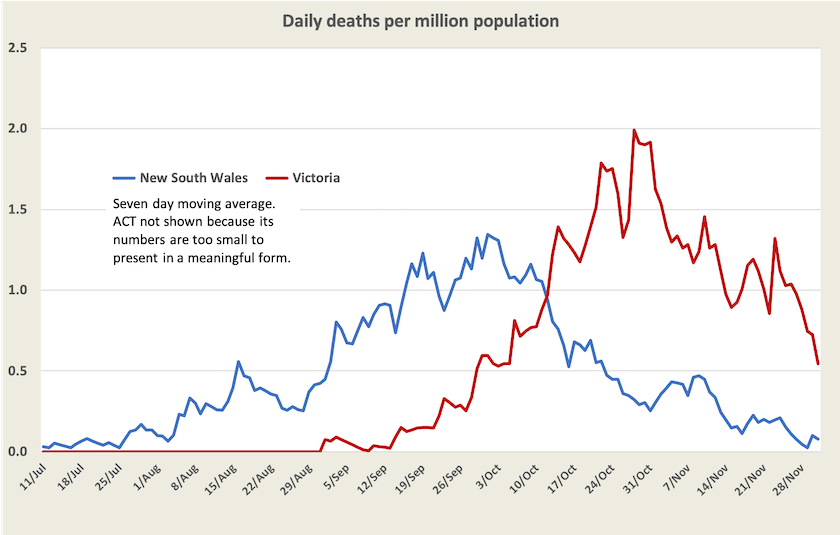

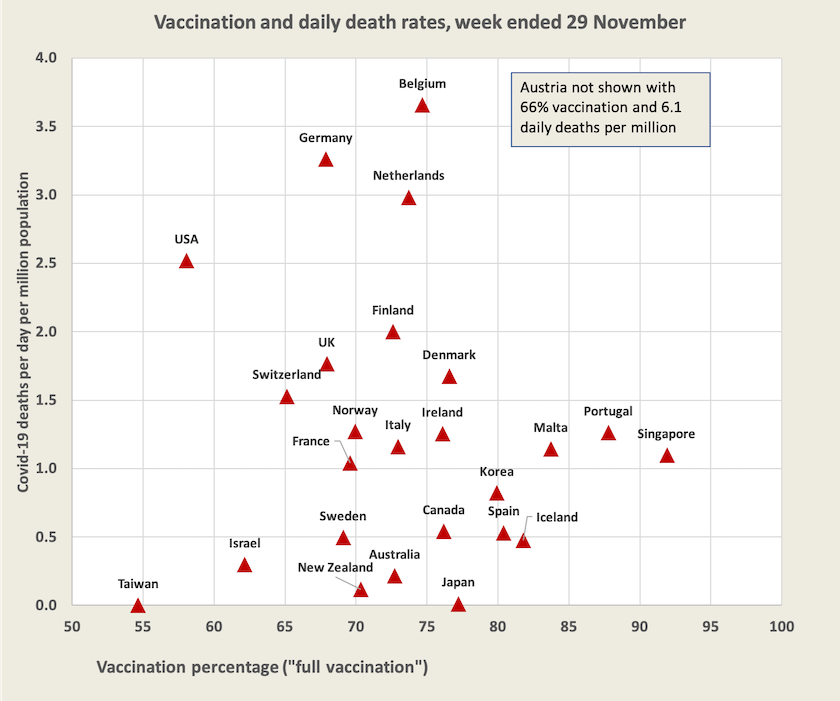

For comparison with other countries, the following scatter diagram, an update of earlier charts, shows vaccination levels and daily death rates for high-income countries over the week to November 29.

Australia’s dot on that diagram is a record of where the whole nation stands. If we were to consider only that part of Australia where the virus has been circulating – New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT – our dot would lie a little to the northeast, between Canada’s and Japan’s, with 77 percent vaccination and 0.3 daily deaths per million. In comparison with other countries we are doing well in terms of vaccinations and deaths, but we are not leading the pack.

There is much speculation as to whether the high rates in European countries that had been doing so well relate to the onset of winter or to other factors. Israel is another puzzling case, with its low death rate and low level of vaccination. This is possibly because it is now considering three shots to comprise “full vaccination” and has prioritized the third shot for the elderly and frail.

Vaccination progress

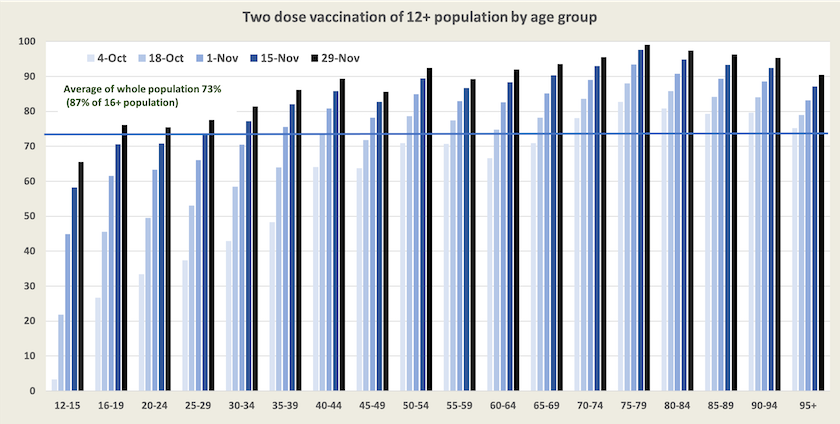

It would help public understanding if politicians, particularly the prime minister, stopped talking about our marvellous “90 percent” vaccination level, claiming it is among the world’s highest. That figure refers only to the population aged 16 and over, and nationally we aren’t there yet. Our national level, across the whole population, is about 73 percent. As pointed out in the above section our vaccination level is about 77 percent where the virus is circulating. In the other five jurisdictions it’s about 65 percent. Out of those eligible for vaccination – those aged 12 or more – vaccination levels are at 97 percent in the ACT and 90 percent in New South Wales and Victoria. Readers can speculate on the reasons for Canberra’s high level of vaccination.

Many countries are well ahead of us in vaccination, including Singapore, Portugal, Spain, Korea and Iceland where vaccination levels are above 77 percent of the population.

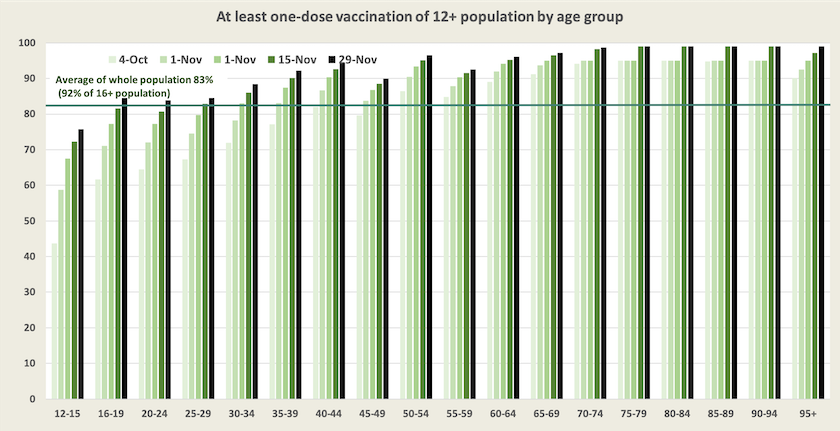

National progress in vaccination is shown in the two charts below. The age profile in both charts is notable: people in the 16 to 29 age brackets are comparatively unvaccinated, and their progress seems to have slowed, particularly in the last two weeks. (Those aged 12-15 were latecomers for eligibility). This should be of concern for policymakers, because although they are less likely than older people to suffer severe symptoms or deaths, young adults are generally mobile, and are often in busy workplaces or education institutions.

If we consider the vaccination data provided by the ABC’s Digital Story Innovation Team, the best vaccination level we may achieve is around 93 percent of the eligible population. This back-of-the-envelope estimate is based on New South Wales having reached 92.7 percent first dose among those aged 16 or more, while their new uptake of first-dose vaccination is now down to 0.02 percent per day, or virtually stalled. Victoria’s vaccination level is lower (91.0 percent), but their daily uptake is still considerably faster.

Until children aged 5 to 11 are included, the best we might hope for is a national level of around 77 percent two-dose vaccination, but soon we will be considering our uptake of three-dose vaccination.

Fake news

“Vaccinated people face certain death”.

Of course they do, as does everybody else. The anti-vaxxers’ headlines are not quite so obviously ridiculous, but they come close, when, for example, they point out that in country X most people who develop Covid-19 have been vaccinated – an inevitability when almost everybody is vaccinated. Writing in The ConversationJacques Raubenheimer describes how data on vaccinations, infections and deaths can be manipulated to give the impression that vaccines don’t work. As a counter he gives a few basic lessons in using data to make better-informed assessments: Covid death data can be shared to make it look like vaccines don’t work, or worse – but that’s not the whole picture.

Raubenheimer is writing about misuse of accurate data. There are also anti vaxxers who simply make stuff up.

On the ABC Breakfast program Clive Palmer spoke in support of the so-called “freedom” movement, claiming, for example, that 500000 people marched in Melbourne, and 150000 marched in Sydney against vaccine mandates, vaccine passports and lockdowns, and that the presently approved Covid-19 vaccines haven’t gone through any testing. (12 minutes) On the same Breakfast program the following day Max Chalmers went through some of Clive Palmer’s claims, suggesting, for example, that the demonstrations in Melbourne and Sydney were more like 10000 strong: Clive Palmer's Covid facts – the backstory with Max Chalmers. (6 minutes)

However many there were demonstrating, Denis Moriarty, who has generally supported people’s rights to take to the streets, does not support these protests. Writing in the Canberra Times he notes that the protesters’ arguments have no merits, and that they “don’t seem to recognise the concept of social responsibility”. He understands that they have resentments, but these resentments are not in response to a package of core beliefs. That mood of resentment “is attracting a toxic maelstrom of American borrowings, where the paranoid fantasies of QAnon and the Trumpists are cut and pasted into Australian society without much concern as to whether they have anything to do with us”.