The economy

What will happen when we (eventually) re-open our borders to immigrants?

In a 3-minute video Alan Kohler pulls together the economics of immigration, wages and house prices: Australia is about to reopen to migrants. It could exacerbate some economic risks. On one side are Australian businesses who would like to see all those temporary immigrants join the workforce and keep wages down, particularly in the hospitality and food service industries, and they would like to see population growth to compensate for our miserable productivity performance. On the other side are workers who haven’t had a real pay rise for years, first-home buyers, and those concerned about congestion and other stresses on public services resulting from population growth.

It’s an impressive presentation. Most university lecturers would take at least three classes to cover the same ground as clearly as Kohler manages.

On the same issue Henry Sherrell and Brendan Coates of the Grattan Institute, writing in The Conversation, warn that Australia’s new agricultural work visa could supercharge the forces of exploitation. Immigrant workers in agricultural industries are in a very weak bargaining position compared with their employers.

Sherrell and Coates believe that rather than bringing in low-paid-low-skill temporary immigrants, we should expand our intake of well-qualified immigrants. Such a priority is not in line with the Morrison government’s thinking, however.

Have our capitalists lost their animal spirits?

In a speech to the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), Reserve Bank Assistant Governor Luci Ellis sums up some of Australia’s structural weaknesses – declining non-mining business investment, weakening labour productivity, and low turnover of labour and businesses. She concludes that capitalism in Australia has lost some of its dynamism and appetite for risk-taking. She also suggests that gains from new technologies are becoming harder to realize: we have picked the low-hanging fruit, but further technology-based productivity gains will require more IT skills than we have on hand.

Although her speech is titled Innovation and dynamism in the post-pandemic world, the trends she presents go back some decades.

She asks whether the experience of the pandemic has reinforced this cautious, risk-averse culture, or whether we will emerge from the pandemic with a more dynamic and innovative economy. She doesn’t mention the influence of the dead hand of the Morrison government’s political agenda of yielding to rent-seekers, coddling the finance sector, and protecting established fossil-fuel based industries, as possible causes of our complacent business culture.

Summarising and commenting on Ellis’s speech Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, challenges Morrison’s idea that Australian capitalism is governed by a “can do” culture, contrasting with a “don’t do” government culture: “Can-do capitalism” is delivering less than it used to. Here are 3 reasons why. As economists such as Mariana Mazzucato stress, the public sector can be just as innovative and entrepreneurial as the private sector, and is often the leader of structural change.

Is inflation coming back to haunt us?

A reader has drawn attention to an article in the Financial Times Inflation: is now the time to get worried? The writer, Chris Giles, compares inflation forecasts in G7 countries made in January and again in November, noting that for all countries apart from Japan the November forecasts predict significantly higher inflation.

Giles notes that there are many temporary inflation drivers, including energy prices and supply bottlenecks. But there are also signs of more enduring drivers of demand-pull inflation. For a long time central banks have been concerned to stave off deflation, and have been aiming to stimulate economies hit by Covid-19, but perhaps they should now be taking a more deflationary stance.

Lest you think he is warning about some Zimbabwe or Venezuela-type inflationary outbreak, the forecasts he is referring to are in the 3 to 4 percent range. Such price rises, if accompanied by rises in nominal interest rates and in wages, may help unstick some prices and help those who have unwisely borrowed too much for housing to pay off some of their debt.

(Warning: The Financial Times seems to regard successive clicks on the same article as a new request, and may block you if you try to re-load it. If you want to read the article carefully I suggest you print it.)

National accounts

The ABS released the September Quarter National Accounts on Friday, reflecting the influence of the resurgence of Covid-19 in New South Wales and Victoria. Its macro figures were a little better than market expectations. GDP fell by 1.9 percent in the quarter: it would have fallen further but for temporarily strong demand for coal, LNG and meat, and a decline in imports associated with supply-chain problems.

A finding that may escape the attention of Coalition-aligned media is that in the September quarter state final demand fell by 6.5 percent in New South Wales and by 1.4 percent in Victoria, the states with the Covid-19 outbreak, while rising in all other states. This is not to suggest that the Victorian government is better at economic management than the New South Wales government. Rather this difference reflects the fact that the New South Wales outbreak peaked during the September quarter, while it came later to Victoria (having crossed the border from New South Wales). Victoria’s peak was in October and does not show up in the September national accounts: it will show up in the December quarter accounts.

We might recall that the New South Wales outbreak started with an unvaccinated limousine driver serving foreign airline crews. Early intervention with a firm but short lockdown, as advised by public health experts, may have arrested the outbreak, and allowed New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT to continue without restrictions until their populations were well-vaccinated. Morrison, however, in response to so-called “business interests” (lobbyists whose impatience and greed blind them to consideration of the economic effects of an outbreak), hectored the Berejiklian government not to act on the early cases. While the cost in economic output is revealed in these national accounts, the cost in life is partly measured in mortality statistics: so far this outbreak has cost 1100 deaths in New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT. Had the Morrison government not neglected opportunities to order vaccines last year, all of Australia would have been able to open up the economy several months ago. This is the contraction we didn’t have to have.

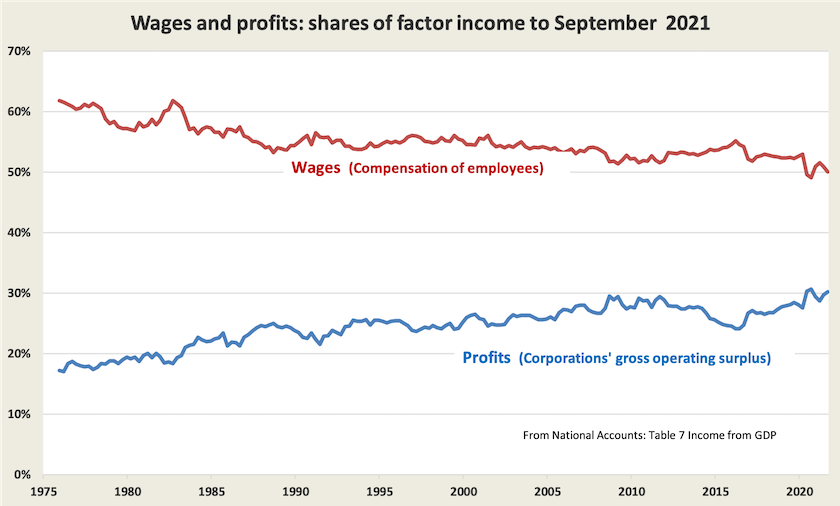

Another finding that the media seem to have missed is that there has been no let-up in the distribution of income going to profits and wages. Between them the pandemic and the Morrison government have been kind to those who live off profits and tough on workers, as is shown in the graph below. In the last two years there has been a sharp rise in the share of income going to profits and a corresponding fall in the share going to wages.

A comprehensive description of the trends in the labour market is provided by Simon Küstenmacher, “The Stats Guy” who writes for The New Daily: Can we unsqueeze the financial pressures on Australian workers?. He describes not only the financial squeeze on most workers, but also practical and affordable policy measures to alleviate it – measures that the Coalition is unlikely to adopt.

The case for an early childhood guarantee

The Centre for Policy Development has released its proposal for a universal early childhood program: Starting better: a guarantee for young children and families.

While there have been many calls for stronger government support for child care and other measures such as paid parental leave, this report is a call for a new policy approach. The authors have engaged in thorough research and consultation to develop the case for “a guarantee for young children (from birth to age eight) and their families, based on the principle that cost should never be a barrier to essential early childhood services”. It’s an extension of the established principle that Australians are already guaranteed free quality schooling up to Year 12.

Although such a guarantee would be of benefit to families coping with the most financially difficult years of their lives, the authors see it as far more than an extension of the social wage. “A guarantee for young children and families is one of the best ways to address disadvantage because it increases the prospects for children to thrive, learn and earn throughout their lifetimes”. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the authors’ calculations reveal that outlays on a guarantee would have significant net economic benefits in terms of a future workforce capable of making greater contributions to the economy and making less demand on government programs of income support, health and criminal justice.

Housing

There are three publications on housing that may be of interest to readers:

Brendan Coates of the Grattan Institute has a short article on public housing, and calls for a social housing future fund. Australia’s stock of public housing and community housing has hardly grown over the last 20 years, while our population has grown by 30 percent over the same period. He takes the reader through the financial flows that would see the Commonwealth take the lead in investing in social housing. It’s a solid business case (but probably unappealing to a government that fails to distinguish between recurrent and capital outlays.)

The Australian Housing and Research Institute has produced a major report on regional aspects of homelessness: Estimating the population at risk of homelessness in small areas. It won’t come as a surprise to those who are familiar with concentrations of homeless people in urban regions in or close to CBDs. But less visible to most Australians is the incidence of homelessness in non-metropolitan regions, particularly remote and outback regions in all states and the Northern Territory.

The ABC’s Michael Janda has a short article on the likely trajectory of housing prices over the next few years: House prices depend on interest rates: as one goes up, the other will fall. The relationship between interest rates and asset prices is fairly standard economics, but he goes into some of the finer points of the likely behaviour of banks (who are raising interest rates), the Reserve Bank (trying to adhere to a promise to hold the cash rate), the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (wisely making it harder for people to take out large loans), house owners (who aren’t selling) and state governments (who aren’t releasing much land). A likely development will be some modest rise in prices for one or two years, followed by a slow contraction.

Bankers behaving badly

On the ABC’s Background Briefing Reporter Mario Christodoulou draws our attention to The biggest financial scandal you've never heard of, describing a tax investigation in which Macquarie is involved. The specific case is about a fault in German tax law, which has unintentionally allowed investors to double-count certain tax deductions.

The 40-minute program covers several themes, including the credentials and character of people appointed to financial regulatory agencies, the fine distinction between complying with the law and complying with the intention of the law, and the responsibility of bankers when they lend money to people who will use it for illegal purposes.

Christodoulou also draws our attention to the most important issue in tax evasion and aggressive tax minimisation – their impact on public services. If someone breaks into our local school, breaking windows, vandalising equipment and stealing computers, we are understandably annoyed, and want the people involved brought to justice. But by comparison, when the theft from the public is through fraud or tax evasion, we seem to be much less concerned, although the damage to our public services is much greater than anything that can be wrought by a few irresponsible delinquents.

Pubs and clubs behaving badly

While our attention has been drawn to money laundering and other malfeasance in casinos, we have been paying less attention to what’s going on in pubs and clubs with poker machines.

Writing in The Sydney Morning Herald Nick McKenzie and Joel Tozer describe how poker machines in these more modest venues have been used for money laundering: $1 billion and counting: investigator reveals size of poker machine crime. They quote New South Wales gaming investigator David Byrne who warns about the parties and groups who need to disguise their ill-gotten gains as gambling winnings – people involved in child exploitation, human trafficking, firearms trafficking and terrorism funding. Byrne has called on the state government to launch an inquiry into the industry – an inquiry with the same scope as that faced by Crown Casino.

McKenzie and Tozer also write about the tremendous pressure the gambling lobby has used to stymie any proposals for reform, a theme they take up in another article The money laundry: pubs and clubs the next frontier for crime. They describe how, through a combination of donations and threats, the gambling lobbies have brought both the Coalition and Labor parties on side.

Although McKenzie and Tozer’s articles are mainly about what’s going on in New South Wales, they also mention similar activities and similar political influence in other states. In a separate investigation, the ABC’s Emily Baker describes how, in Tasmania in 2018, when Labor proposed reform of poker machine gambling, a hospitality lobby group spent $0.9 million on donations to the Liberal Party and on campaigns against Labor. The industry has consequently been rewarded with $15 million in government funding: Tasmanian Hospitality Association receives millions in grants after lobbying against Greens, Labor.

(The hospitality industry’s claim against reformers is that pubs and clubs are significant employers, particularly in the poorer regions. “Save our jobs: vote Liberal” read the banners in the 2018 Tasmanian campaign. That message ignores the fact that the money lost through poker machines, which are concentrated in poorer regions, would have generally been supporting regional economies in more productive and less damaging ways.)

Why we have an antiquated rail system

The bridge is even older than the locomotive

Draw a line through Brisbane, the Gold Coast, Newcastle, Sydney, Wollongong, Canberra, Melbourne, Geelong and Adelaide, and you have laid out the track for a high-speed rail line serving 17 million people (around the population of The Netherlands).

So why, in spite of decades of discussion, congestion in our main airports, and the need to electrify transport, do we still not have a high-speed rail service?

Writing for the Grattan Institute, Marion Terrill provides the reason. When governments or consultants employed by governments evaluate high-speed rail projects they require such projects to show an unrealistically high financial return on investment. They set as a target a real (inflation-adjusted) return of 7 percent, even though the real borrowing rate for the government is much lower. (In fact the government’s real cost of funds is probably negative at present). But when high-speed rail projects are evaluated with a more reasonable target return of 4 percent they start to look viable. (Economists will realise that she is referring to the discount rates or internal rate of return applied to infrastructure projects.)

Her article titled High-speed rail dreaming is a fast track to nowhere seems to have an anti-high speed rail bias: perhaps her time in the Commonwealth Treasury has left a mark on her thinking. But she does question why successive Commonwealth administrations have adhered to that 7 percent rate for all significant infrastructure projects. (The answer may lie in the political significance of the budgetary cash deficit. As Miriam Lyons and I explain in Governomics: can we afford small government?, governments’ obsession with the budgetary cash deficit rather than the national balance sheet, their use of certain dysfunctional accounting conventions, and their “small government” obsession, all work against public investment.)

Terrill’s article also reminds us that if it manages to get Morrison and his cronies out of office, Labor will create a high-speed rail authority. Labor makes no specific promises but at least they would get it back on the agenda.

Let’s have a tax on beards

On last week’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed Michael Keen of the IMF and Joel Slemrod of the University of Michigan about taxation: Tax rebels and the lessons they hold for today. We might expect two such experts to take us through the standard academic coverage of taxation – allocative efficiency, administrative efficiency, equity, ability to pay and so on. They touch on these issues, but their story is mainly about the history and political economy of taxation over thousands of years, and how our taxation arrangements reflect and influence our cultural norms. It’s in this context that Slemrod describes Russia’s beard tax imposed in 1698.

They are authors of Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom Through the Ages.