Pandemic politics

How is vaccination really going?

On the same day that Morrison denied having ever told a lie in public life (“I don’t believe I have”), he was quoted on Sky News saying that in Australia we have passed the 90 percent first-dose vaccination rate. Using weird metaphors about grappling hooks he went on to say that every state has achieved 80 percent first-dose vaccination, claiming that at 80 percent vaccination states can open up and safely stay open.

The actual figures are that we have achieved 90 percent first-dose vaccination and 80 percent vaccination only of Australians aged 16 or older. As at November 16, a few days after Morrison made his comments, our actual vaccination rate, across the whole population, is 70 percent, and the only state or territory to have reached 80 percent first-dose level is the ACT (83 percent). The agreement that the states had entered into never considered an 80 percent first-dose level to be adequate for lifting restrictions.

That 70 percent is a national average. In New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT, where the virus is present, if these stats are considered as a whole the vaccination level is 75 percent, and almost 80 percent have a first dose. In the other five states and territories, considered as a whole, the vaccination level is 60 percent.

If we can achieve 80 percent nationally we would be ahead of the pack, with a level comparable to Spain (80 percent) and Chile (82 percent), well ahead of the USA (58 percent) and Germany (67 percent), but still behind Singapore (85 percent) and Portugal (88 percent).

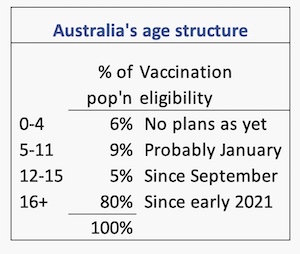

At present in Australia everyone aged 12 or over, 85 percent of our population, is eligible for vaccination. That means our theoretical maximum level of vaccination, based on present eligibility, is 85 per cent.

Some may take the attitude that once we reach 80 percent it’s not worth chasing that remaining 5 percent, but that 5 percent refers to 1.3 million unvaccinated people. Each percentage point above 80 percent reduces by a quarter of a million the number of people who are likely to get the most severe infections and spread the virus, and who themselves are most likely to put high demands on our heath system. That’s why it’s important for those with a public voice to present the data as clearly as possible, without falsely inflating the numbers for political purposes.

It is now clear that children aged 5 to 11 will have to wait until at least January to be eligible for vaccination while the Therapeutic Goods Administration reviews efficacy and safety data. If that approval occurs 94 percent of the population will be eligible for vaccination. A snapshot of our age structure, classified along vaccination eligibility bands, is shown alongside.

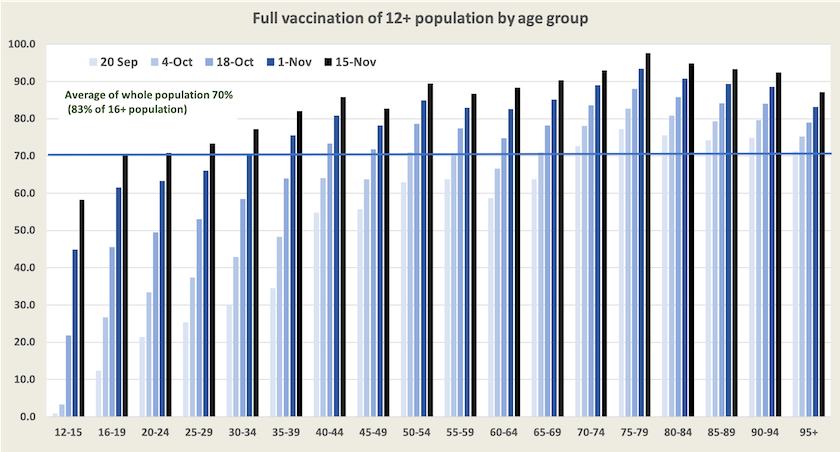

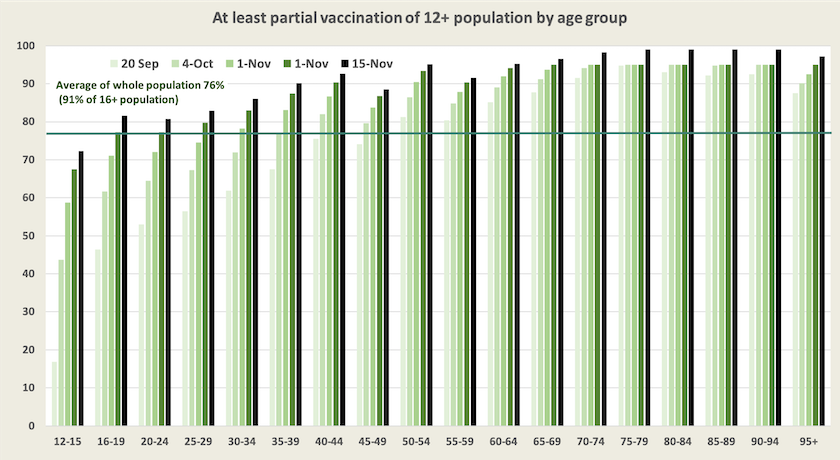

The two graphs below, updates of graphs presented fortnightly, show our vaccine progress over the last two months. It is notable that older people are still catching up: presumably these are in the states so far protected from the virus. The very steep rise in the 12-15 group is explained by the fact that they have been eligible for vaccination only since early September.

The first-dose chart seems to indicate that a whole bunch of people over 70 has suddenly decided to get vaccinated, but that impression results from a reclassification by the Department of Health.

Dealing with the unvaccinated

Those who refuse to be vaccinated with their strident demonstrations and obstinate behaviour have done nothing to endear themselves to the community.

In Singapore the unvaccinated who need hospitalization will be hit with hefty bills. In Austria, where the vaccination rate is stuck at around 63 percent, the government has imposed strict lockdown rules on the unvaccinated, similar to the rules applied to the whole population in New South Wales and Victoria at the height of the pandemic. Apart from work, grocery shopping, exercise or getting vaccinated the unvaccinated in Austria are confined to their homes.

Stephen Duckett, writing in The Conversation, covers issues associated with vaccination incentives, particularly the Singapore model, about which some people are enthusiastic: People who choose not to get vaccinated shouldn’t have to pay for COVID care in hospital. He points out that vaccination “suffers from a distinct social gradient. Poorer people and those less well educated have lower rates of vaccination”. Governments, particularly the federal government, have done a poor job at reaching these groups.

He doesn’t oppose using strong incentives to encourage vaccination, but he stresses that “the health system needs to be there for everyone, not just people who look like us, nor just for people we like, nor just for people whose choices we endorse.”

International comparisons

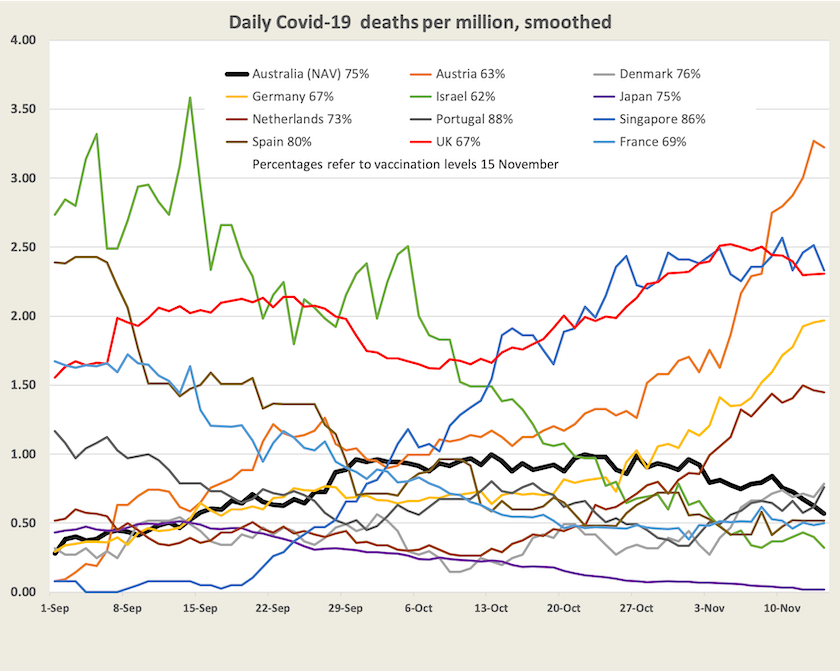

A great deal of publicity has been given to surging cases in Europe and in Singapore, in spite of high levels of vaccination. In many countries cases started to rise in mid-October, and a rise in deaths has followed. But different countries have different experiences.

In order to illustrate what’s happening I have constructed a graph of death rates from Covid-19 per million for a number of large “developed” countries from September 1, when many countries started to open up, to November 15. They are in the colored lines, and in a thick black line, for comparison, is Australia’ daily death rate, but it isn’t really Australia: it’s a combination of New South Wales, the ACT and Victoria – Australia (NAV).

There is no general trend, but there are patterns which I will go through color-by-color:

- Germany (yellow), Austria (orange), Netherlands (light brown). Comparatively low vaccination levels. Significant surges in deaths.

- Spain (dark brown), Portugal (dark gray), Denmark (light gray). High vaccination levels. Rises in all 3 countries, but from a low base, not a surge. Deaths in all 3 countries around 0.5 per million, the same as Australia (NAV).

- France (light blue) and Israel (green). Neither country highly vaccinated, significant falls to low levels.

- The UK (red). Low vaccination rate, never really got it under control. High death rate.

- Japan (purple). Reasonably high vaccination. Deaths declining since the Olympics.

- Singapore (dark blue). Very high vaccination rate, very large surge in deaths.

- Not shown is the USA, 56 percent vaccinated, and daily deaths have fallen from 6.3 per million in September to 3.5 per million. (If it were included it would just peek in at the top right-hand corner of the graph.

A cautious observation is that the lower the level of vaccination the worse has been the rise in deaths, but Japan, Israel and Singapore do not fit that pattern.

On the ABC’s Breakfast program Norman Swan puts the European surge down in part to waning effectiveness of vaccines, particularly the Astra-Zeneca vaccine: COVID numbers surge in Europe once again. Also Israel was perhaps one of the first countries to experience waning effectiveness, but in response it has been one of the first to encourage people to have boosters. France is re-defining “full vaccination” to mean 3-dose cover, but that re-definition is too recent to explain its fall in deaths. Japan is a puzzle. It is possible that it is attributing deaths of people with co-morbidities to conditions other than Covid-19, but that couldn’t explain the full picture.

Swan explains that in most European countries there has been more vaccine hesitancy than in Australia, which is one reason countries are resorting to strong measures to encourage vaccination. But he stresses that Europe’s experience carries a warning of what can happen as the weather gets colder.

Singapore is another country that goes against the experience of other countries. Unlike Germany, Austria and the UK, which have rural regions with low rates of vaccination, Singapore is a city-state. And it has no cold season. The ABC’s Anne Barker provides some tentative explanations: Australia might be on its coronavirus 'honeymoon'. Singapore shows what could happen next. Unlike other countries, in Singapore older people constitute a significant proportion of the unvaccinated, and as an early mover, it may be experiencing waning effectiveness. A glance at the Ministry of Health statistics confirms that the elderly unvaccinated are being admitted to hospital and dying.

The next stage – living with Covid

Provided we reach and sustain high vaccination levels, and provided no more contagious or dangerous variants of Covid-19 emerge, we should soon be “living with Covid”.

In an editorial published in the Medical Journal of Australia – On entering Australia’s third year with Covid‐19 – Steven Duckett and Brett Sutton point out that while our policymakers have been very concerned initially to keep Covid-19 out of the country, then to get us vaccinated, and most recently to chart an “opening up” path, they have tended to assume that we will effortlessly ease into the recovery phase.

But there are many administrative matters to deal with, such as putting telehealth on a firmer footing, and making sure we have quarantine and vaccine readiness. And more important, there is a need to recognize and deal with the economic and psychological damage wrought by Covid-19, which “affected Australia very unevenly, with poorer outcomes for those at greatest disadvantage”. They stress that “the recovery phase needs to rebuild community and system resilience and redress disadvantage exacerbated by Covid-19”. Our experience with Covid-19 has confirmed the importance of public health through demonstrating the systemic interrelationships between disease and disadvantage. It would be costly if we neglect to learn from our experience.

In a similar vein but in a broader context Global Access Partners and the Institute for Integrated Research have published a paper Australia – a complacent nation, noting that the pandemic has exposed weaknesses in our social and political systems. Our ability to deal with shocks such as Covid-19 and climate change depends on the strength of our social cohesion:

Social cohesion enables and derives from social activity, especially collaborative and supportive activity built on a foundation of trust. Strong, trusting social bonds that survive and thrive in the face of differences of opinions, beliefs, life circumstances and living conditions are crucial for a society or community to be ‘resilient’, especially when confronted by sudden change or catastrophic threats or events.

Sources

See the separate web page of hyperlinks to generally reliable information and analysis about Covid-19, including data on vaccination and the WHO Covid-19 epidemiological updates.