Pandemic politics

Vaccination progress

Progress in the New South Wales, Victoria, ACT bubble

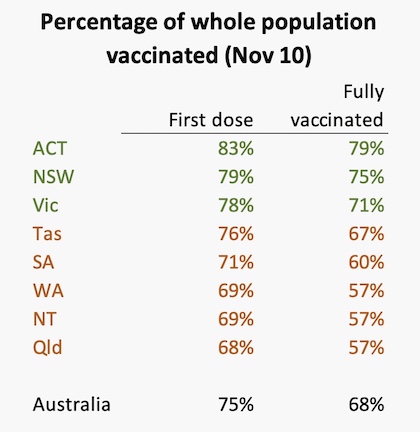

We have made good progress in vaccination, but we would do well to ignore Morrison’s hype about having reached a vaccination rate of 80 percent. That figure refers only to Australians aged 16 or older, who comprise 80 percent of our population. It’s not a particularly useful measure, because people aged 12 or older are eligible for vaccination. Our true rate of vaccination across the whole population is around 68 percent. As can be seen in the table below, vaccination rates are much higher in states where the virus is spreading (New South Wales, the ACT and Victoria).

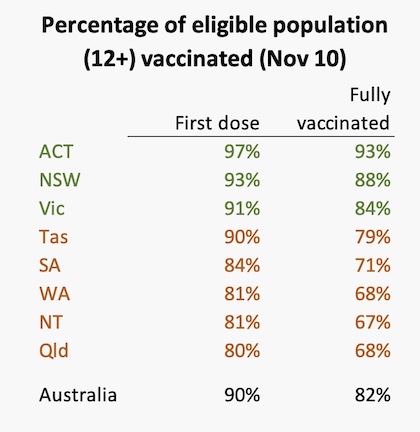

To relate these figures to the claims of state governments, I have prepared a table of vaccination rates for the population presently eligible for vaccination – everyone aged 12 or over.[1]

We’re doing well, but we have some way to go. If the nation could achieve the level of vaccination the ACT has achieved in its first dose, assuming all who have had a first dose go on to have a second dose, that would give a national rate of 83 percent (the ACT first dose figure), just short of a theoretical maximum of 85 percent if everyone presently eligible for vaccination were vaccinated. Only a few countries, Singapore, Iceland, and Portugal are achieving such high rates.

There is evidence that vaccination rates in New South Wales are slowing down. In the latest week the New South Wales first-dose vaccination level has risen by only 0.37 percent. It may take a significant effort to get our national rate much above 80 percent, unless and until we vaccinate people younger than 12.

Younger people and schools

Understandably, in those states where the virus is present, attention is turning towards rising infections among young people – those aged 12 to 15 who have been eligible for vaccination since September 13 but are not yet fully vaccinated, and those aged up to 11 who are not yet eligible for vaccination. The ABC’s analyst Casey Briggs has a 4-minute explanation of the infection situation in New South Wales and Victoria. In the ACT the government reports that the average age of those now infected with Covid-19 is 17. Infection among adults is falling, but is still rising among young people, and because schools are now open they are the spots from which the virus could propagate.

That still leaves children under 12, comprising 15 percent of the population, unvaccinated. There will probably be approval of vaccines for those aged 5-11. If that happens 94 percent of the population would be eligible for vaccination. Also the pharmaceutical firms are conducting early-stage trials of vaccines for infants aged up to 4. On the 730 Report on Monday night Norman Swan discussed the case for vaccinating the 5-11 group. Emma McBryde of James Cook University hinted that if we can get the same high level of vaccination among children as we have with adults, we might be approaching herd protection, in spite of the high R of the Delta variant. (The ABC’s web page for the program gives the impression that the case for vaccinating children is not settled, but on watching the 6-minute program it’s fairly clear that even for young people the benefits outweigh any possible risk, and that’s before considering the benefits for the wider community.)

Further opening upWhile the governments of states planning to open up in the next few weeks (all apart from Western Australia) will have an eye on what’s happening in New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT, they will also have regard to the latest Doherty modelling (available on its website). It’s an update of its previous models, and like those models it emphasizes that even at high rates of vaccination there will still have to be a certain level of public health and safety measures.

Under pressure from the Commonwealth and commercial interests, these states are being urged to open up as soon as they reach a vaccination level at which the transmission potential can be held at 1.0. That is at 80 percent of the 16+ population, according to the Doherty model. Morrison is already hectoring Western Australia to open its borders at that level, rather than waiting until 90 percent of the 12+ population is vaccinated as the state government is planning.

The trouble with an approach designed to maintain R at 1.0 is that it puts an ongoing load on the health system, and in any case a level of 1.0 is an unstable situation: in the real world it is not possible to keep a system so finely balanced. If R can be brought down well below 1.0 then outbreaks, when they occur, are likely to be suppressed fairly quickly. Unfortunately there are many in business lobbies who believe that the prime function of the health care system is to ensure that corporations can maximize their profits.

One area where the Doherty modelling can guide governments is about dealing with outbreaks in schools, as explained by Sarah Martin writing in The Guardian. She explains it a little more clearly than it is explained in the Doherty document – Daily Covid tests being considered to replace home quarantine for school students. When there is an outbreak in a school only those infected would isolate, while those classified as contacts would continue at school while undergoing regular antigen tests. (A more effective approach would be to ensure that children aged 5 to 11 are vaccinated.)

Once again, it is necessary to stress that most discussion about vaccination concerns state averages. Within states there are significant variations in vaccination, partly along urban-rural lines. The latest Doherty model has a specific section on the risks faced by indigenous Australians living in remote communities, assuming that for them their R0, the virus’s “transmission potential” (reproduction rate) for an unprepared population, is greater than it is for other Australians. Unless children aged from 5 are vaccinated these communities could not be expected to reach an R of 1.0.

Also the ABC’s Catherine Hanrahan has pulled together some informative regional data on vaccination and cases in New South Wales: NSW COVID-19 vaccination data reveals which areas are lagging behind. There are significant regional variations. Other states, particularly Queensland, would be showing similar variations.

How effective is vaccination in Australia?

The New South Wales Government has published a short report on vaccination, infections, hospitalisation, ICU admissions and deaths for the period June 16 (when the present outbreak started) to October 17. It confirms that vaccination has been effective in protecting against infection, serious disease and death. (Obtaining an indicator of protection against spreading the disease is not recorded: that would require a completely different dataset.)

The most striking finding is that only 47 of the 412 who died over that period were fully vaccinated. Of those 47, 29 were residents of aged-care facilities and 18 had “significant” comorbidities. Only 30 of those admitted to ICU were fully vaccinated. It finds that “the rates of COVID-19 ICU admissions or deaths peaked in the fortnight 8 September to 21 September at 0.9 per 100,000 in 2-dose vaccinated people compared to 15.6 per 100 000 in unvaccinated people, a greater than 16-fold difference.”

A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation, based on the 412 deaths over that period, indicates a daily death rate of 0.405 per million state population. Among the vaccinated the daily death rate was 0.046 per million. Scaled up to a national level and an annual rate this would indicate an annual death rate of 440.

This is a rough figure, calculated over a period when infections were rising, but it does suggest that those who are fully vaccinated do not put a high load on the health system. If we achieve a high level of vaccination then although the rate of infection among the unvaccinated will be high, because their absolute numbers will be low, they will not necessarily put a significant load on health resources. (In fact anti-vaxxers in US states with high level of vaccination point out that because more vaccinated people than unvaccinated people are contracting the virus and dying vaccination doesn’t work – correct arithmetic, severely misleading math.)

If we can achieve a high level of vaccination we will be spared the difficult situation where the unvaccinated, because they are clogging up the health care system, are seen to be underserving of treatment. But people’s willingness to pay for others’ obstinacy can wear out. The Singapore government warns that, from December 8, “Covid-19 patients who are unvaccinated by choice will be charged for bills at hospitals and community treatment facilities”.

1. These figures are based on records of 16+ vaccination levels, recorded by state. For the 12-15 population, because only national numbers are published for this group, these have been added to the 16+ percentage. Because this group’s vaccination numbers are probably higher in New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT, the vaccination levels in this table would be understated for these states and overstated for the rest of Australia. The ACT government, for example, reports that 95 percent of its eligible population has been vaccinated, and that they are approaching 100 percent first-dose coverage. ↩

Data sources

See the separate web page of hyperlinks to generally reliable information and analysis about Covid-19, including data on vaccination and the WHO Covid-19 epidemiological updates.