Climate change

To be traded in for an electric model — in 2050

A rebuke to Australia: resubmit

On Wednesday the participants in COP26 issued a draft declaration on the conference’s conclusions and priorities for future action.

No countries are mentioned in the document: if they were it could be re-labelled as a condemnation of Morrison’s pathetic performance at Glasgow. The declaration mentions the need to accelerate the phase-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels, the need to deal with non-CO2 GHG emissions (mainly methane), the need to provide more assistance to “developing” countries, and above all the need to strengthen countries’ 2030 targets. In essence it is demanding that those countries that failed to make adequate 2030 commitments re-submit their proposals, no later than in November next year (by which time we will have had an opportunity to throw this mob out of office).

Writing in Renew Economy Michael Mazengarb summarizes the draft declaration, emphasizing its relevance for Australia. He also draws our attention to the USA-China intention to cooperate on climate change: Glasgow Brief: Draft COP26 deal heaps pressure on Australia as US-China issue rare joint statement.

De-carbonising the economy – we should get on with the job

Standing in a pulpit and waving around a blue-covered pamphlet won’t do anything to reduce GHG emissions. Nor do we have to wait for some as-yet undeveloped technological breakthrough. We should just get on with the job of using the technologies we already have, writes Simon Holmes à Court in The Conversation: Scott Morrison is hiding behind future technologies, when we should just deploy what already exists. If there is widespread deployment of existing technologies the improvements will come along through competitive forces: that’s the technological dynamic of capitalism. A price on carbon would also help to speed up the process. (We are paying dearly for the Liberal Party’s ignorance of economics and business.)

Holmes à Court points out what (almost) everyone knows – that the days are numbered for thermal coal. He also points out that green steel has passed well beyond proof-of-concept stage: metallurgical coal will hang on for a few years but it does not have a secure future.

Electric cars

On Tuesday Morrison, along with Energy Minister Taylor, announced the Coalition’s policy on electric vehicles. Even the title, Driving consumer choice & uptake of low-emissions vehicles, includes a partisan barb. To go on:

Our Plan promised technology not taxes, choices not mandates and driving down the cost of new technologies, and that’s exactly what this Strategy delivers to Australians.

Australians love their family sedan, farmers rely on their trusted ute and our economy counts on trucks and trains to deliver goods from coast to coast.

We will not be forcing Australians out of the car they want to drive or penalising those who can least afford it through bans or taxes. Instead, the Strategy will work to drive down the cost of low and zero emission vehicles, and enhance consumer choice.

That’s right. That horrid un-Australian socialist Shorten intended to make you buy an electric car, something like a Trabant with batteries, from the people’s commission for transport. But the Liberals offer choice! (Unless that’s the choice of an Australian-made car – they closed down that choice in 2017.)

Writing in The Conversation a group of analysts from the University of Queensland explain the policy in plain language, stripped of Liberal Party spin: As the world surges ahead on electric vehicle policy, the Morrison government’s new strategy leaves Australia idling in the garage. Not that there’s much to explain, apart from some promises to spend a little on charging points. Drawing on policies already in place in western European countries. the authors go on to suggest what a proper electric vehicle policy would comprise.

On the ABC’s Breakfast program Behyad Jafari of the Electric Vehicles Council describes the Coalition’s policy as far too little too late. He mounts an economically convincing case for subsidies to early adopters to give the market a boost, as was done in the UK, and as we did with solar panels when generous feed-in tariffs were offered in the early years.

He also draws attention to our failure to implement higher minimum fuel efficiency standards as most other “developed” countries, apart from Russia, have done. As a result Australia has become a dumping ground for dirty vehicles with high fuel consumption. Higher gasoline prices would help consumers and commercial vehicle buyers make more responsible choices of vehicles, however they are powered – electric, diesel or gasoline. (12 minutes)

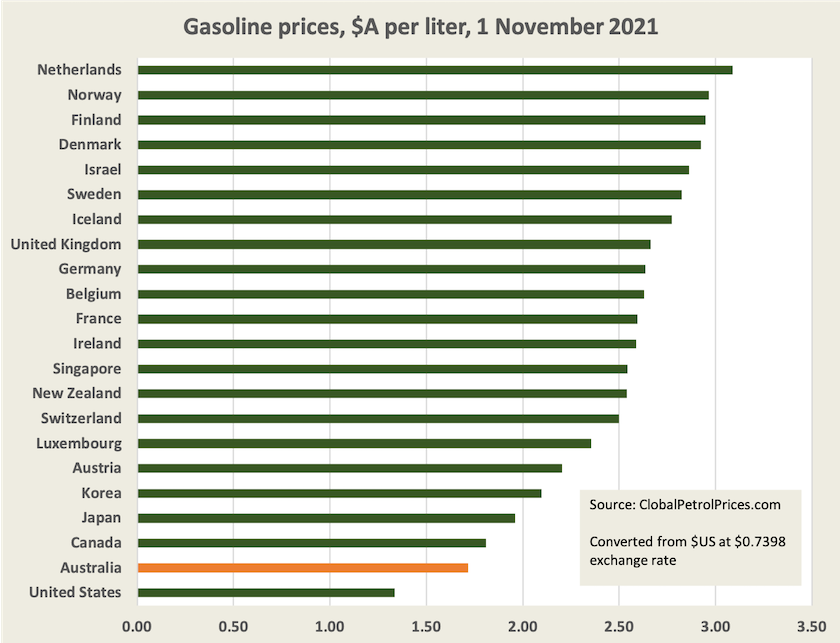

Although Australians grizzle about gasoline prices, the reality is that we have almost the cheapest gasoline prices of all prosperous and “developed” countries, as shown in the table below:

That means there is plenty of capacity to raise gasoline excise to bring our retail prices in line with prices charged in countries governed by adults (to use Jafari’s term). That extra revenue could finance a strong electric vehicle policy, probably through subsidising the purchase price and reducing registration fees. It would have the fiscal virtue of phasing down the amount of money the government collects as gasoline sales phase out, and as the electric vehicle market develops its own standing without needing any subsidy. But to the Liberal Party, the right of Australians to own overweight gas guzzlers, and to drive like angry adolescents, is as sacred as the right to own assault weapons is to Americans.

Green banks

On last week’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed Ian Learmonth, CEO of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, who was still in Glasgow having hosted an event looking at the role that green banks can play in the global transition to net zero. With $A10 billion capitalization, the CEFC is the world’s largest green bank so far, but others are growing.

He explains the CEFC’s role in investing in early-stage ventures. Once these ventures are up and running these companies can go to private markets for capital. In fact the CEFC is already re-cycling funds. He explains how the CEFC meets its requirement to make investments that are both financially viable and able to contribute to reduced GHG emissions, and he describes two of its funded projects, one involving a transmission line into which small renewable generators are supplying electricity, the other an offshoot from a university developing a hydrolyser for the production of hydrogen: Tackling transitions: green banks. (16 minutes)

Our ranking on climate policy

There has been a fair bit of publicity given to our ranking in the Climate Change Performance Index, particularly our score of zero on climate policy. It’s informative to go to the index itself, for it reveals a more thorough picture about how well 64 high- and medium- income countries are dealing with climate change. It has four categories of assessment – GHG emissions, use of renewable energy, energy use, and climate policy. We score poorly on all four criteria, and if anything they let us off lightly, for they seem to be considering only source emissions, not downstream (“Scope 3”) emissions.

Tony Abbott’s legacy – a carbon tax

The ABC’s Ian Verrender credits Tony Abbott with implementing the country’s first, and enduring, carbon tax: Existing carbon markets better than new technology for Australia's net zero goal.

OK, there is no carbon tax, but we do have a carbon pricing scheme. Australian carbon credit units are issued by the Clean Energy Regulator for projects reducing GHG emissions, and these are traded, at a rising price, on the market.

In fact they’re not a “tax”; rather they are a market mechanism bringing into account the economic externality of dumping carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. But when Abbott went to the election in 2013 he deceitfully called Gillard’s carbon pricing scheme a “tax”: Verrender is cheekily using Abbott’s terminology. [1] Verrender’s article takes the reader on a quick tour of the development of carbon markets in Australia: they are here to stay, whatever Abbott or Morrison call them.

1. In everyday language carbon pricing is called a “carbon tax”, and in fact the Gillard government’s carbon price was administered by the Australian Tax Office, in the same way that the ATO administers aspects of superannuation. ↩