Missing revenue: mind the gap

What could be less gripping reading than the annual report of a government agency? But it is worthwhile having a look at the Commissioner of Taxation annual report, particularly pages 60 to 62 on “tax gap estimates”. That is, the extent to which tax collection has fallen short of what would be collected if everyone were compliant with tax regulations and morally committed to contributing to the nation’s common wealth.

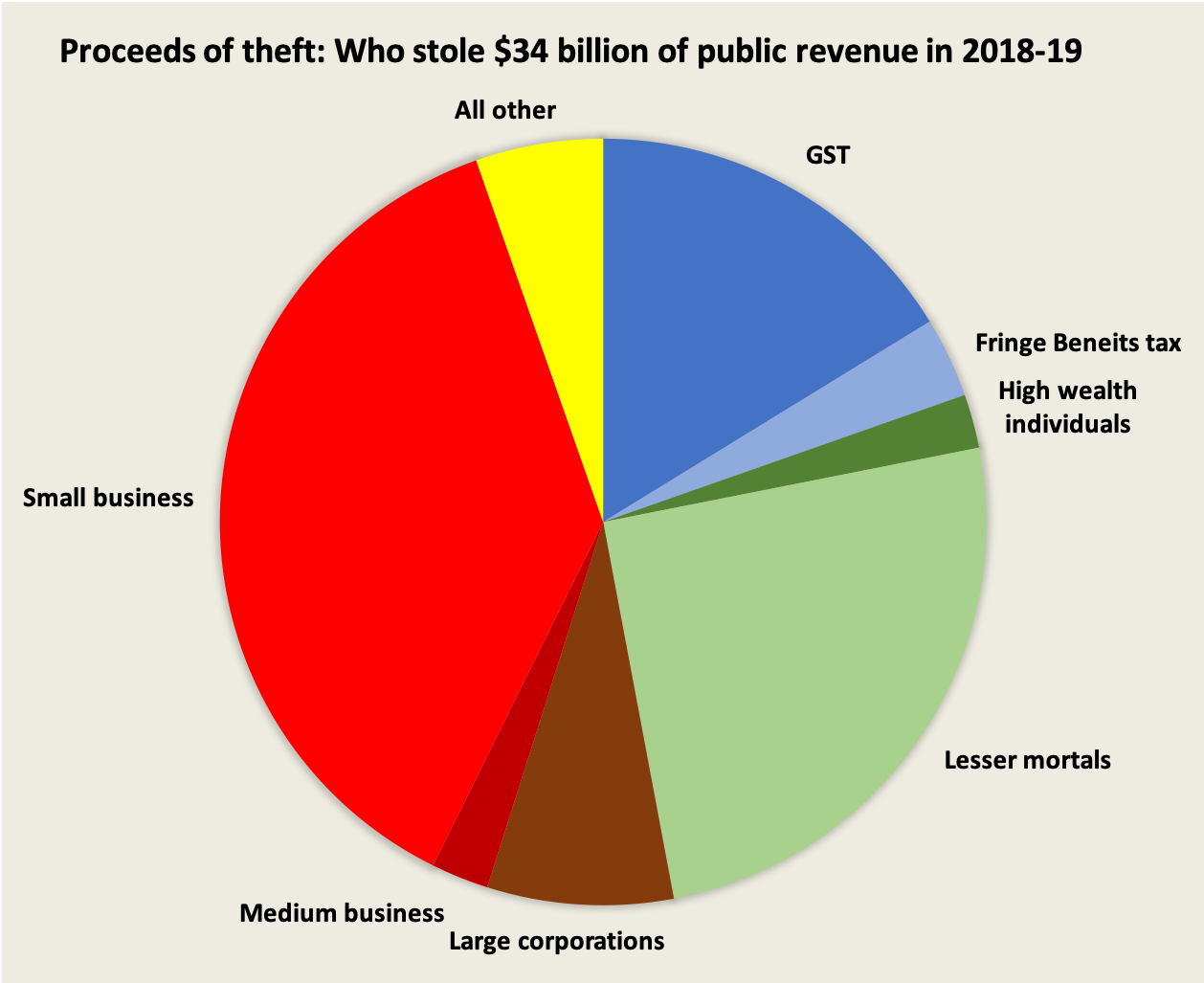

The Tax Office estimates that tax gap to be about $34 billion in 2018-19. That’s the same as the Commonwealth spent on education or on medical services and benefits in the same year.

The chart below shows the Tax Office’s estimates of the gap’s sources – or, in less genteel language, who used what channels to steal from other Australians.

Small business, so greatly praised by Coalition governments, stole the lion’s share ($13 billion or 37 percent). They would also have been involved in much of the $5 billion of under-collected GST.

In addition to that $34 billion in missing tax revenue, the Tax Office also reports on $6 billion of unpaid Superannuation Guarantee Levy and PAYG requirements, stolen from employees. Again, small businesses would have been heavily represented in this theft.

This is not to let large corporations off the hook: the Tax Office reports on compliance with the law – tax evasion, not tax avoidance. While small businesses steal by discounting customers who pay in hard cash to avoid GST, classifying non-involved family members as employees, claiming personal expenses as tax deductions and paying wages in cash without documentation, large businesses don’t have to resort to such illegal practices: they employ corporate lawyers and lobby politicians to make sure that the tax law is on their side.

Coinciding with the release of the annual report, Commissioner Chris Jordan gave an address to the Tax Institute, covering fairly standard ground. He promises that the Tax Office will consider the information revealed in the Pandora Papers. While he talks about the Tax Office’s involvement in administering “Jobkeeper” and early release of superannuation, he makes no mention of the demand that he appear before a standing committee of privileges for not having followed through a Senate order to provide details about businesses receiving “Jobkeeper”.

Inflation

The CPI – 0.8 percent for the quarter and 3.0 percent for the year – came in just at the top of the Reserve Bank’s 2.0 to 3.0 percent comfort range, but it would be rash to say anything about inflation trends at this stage. Price movements have been all over the place during the pandemic. The ABS supplementary measures that factor out large one-off movements came in at 2.1 percent for the year.

There has been a steep rise in gasoline prices (25 percent over the year) and in motor vehicles (6 percent). Also there have been rises in some furniture and related item prices, but these prices may fall back as supply chain problems are solved. New dwelling prices have risen (remember that the CPI does not include land) and these are likely to endure. Clothing and footwear prices fell, presumably as retailers offloaded winter stock that hadn’t moved during lockdowns: this is probably a once-off fall.

While policymakers worry about inflation as an issue in itself, the issue for most people is whether their incomes are keeping up with inflation. Are incomes, particularly wage incomes and basic award wages, rising at 3.0 or even 2.1 percent? And for those paying off a mortgage their concern is about interest rates. Regardless of what the Reserve Bank is doing, long-term market interest rates are rising and mortgage interest rates are rising. It is becoming increasingly evident that the Reserve Bank’s promise to hold its cash rate at 0.1 percent until 2024 will not be kept.

As a comment on the rise in gasoline prices, it should give the government an opportunity to raise excise as a de-facto carbon tax. As wholesale prices start to fall the government can raise excise, thus holding retail prices at present levels. Behavioural economists point out that once the pain of a price rise is experienced it is regarded as a sunk cost. In people’s minds the oil companies are to blame for the rise. A normal gasoline price of $1.70 to $2.00 would send a strong price signal to those who have deferred replacing their vehicles during a long period of reduced mobility. But to the Morrison Government the Toyota HiLux and Ford Ranger have become markers of political identity: real men drive big utes; wimps drive electrics.

Employment and unemployment

How many people looking for work or considering a change in job go to the ABS website to gauge the state of the labour market?

Not many, is a fair guess. The ABC’s business reporter, Gareth Hutchens, explains that the ABS labour force data is not very meaningful for most people: Why doesn't the unemployment rate make sense? Because it's not designed for you. The ABS presents its data in a way that’s designed for employers and government economists, not for jobseekers.

If you’re looking for a job the most useful piece of information would be some indication of your chances of finding one, as indicated, perhaps, by the time people looking for jobs have to spend searching. Such information is available in a limited form, but it requires one to dig around a fair bit. Hutchens presents a suggestion of how the ABS could improve its presentation of labour force data to be more user-friendly.

Also on employment, writing in The Atlantic – The Great Resignation is accelerating – staff writer Derek Thompson observes some labour-market phenomena in the US, as it makes its slow way out of the worst of the pandemic. More people than usual are voluntarily quitting their jobs, and many are quitting the workforce forever. He speculates that the pandemic, and the ways we have adjusted to it, may have downgraded paid work as the centrepiece of people’s identity.

Pandemics have consequences, he points out. But what are he and others observing: a frictional phenomenon as wages and working conditions take time to catch up with technological and demographic changes, or a real re-think of how we view paid work in relation to other domains of our lives?

Immigration

This week Crispin Hull devoted his weekly Canberra Times column to immigration.

The established wisdom, promoted by business interests and rarely questioned, is that as we get over Covid-19 we should return to a high level of immigration to bring in people with essential skills, to give the economy a boost, and to offset the demographic trend of a higher dependency ratio in an ageing population.

Hull pulls apart and dismisses all three arguments.

Businesses want the economy to grow, but what counts for people’s material welfare is not our national income (usually measured by GDP) but income per head. “Better to be richer in a smaller economy than poorer in a larger one. But try telling that to business interests” he writes.

This fortnight’s Essential poll has a number of questions on immigration. Over the last few years Australians have generally believed (50 to 64 percent) that immigration levels are too high, but that belief has fallen to 37 percent.

There are partisan differences: Coalition supporters are more likely to believe that immigration is too high than Labor supporters. But there is a general concern that “increasing immigration levels would add more pressure on the housing system and infrastructure”. This concern is highest among older people, even though younger people are more likely to bear the consequences of immigration pushing up house prices.

Essential finds that we don’t think much of using temporary work visas as a means to suppress wages: there is 72 percent agreement with the statement “temporary work visas should be used to cover genuine skills shortages, not to provide cheap labour” and there is 67 percent agreement with the statement “Everyone who works in Australia should be entitled to the same pay and working conditions regardless of their visa status”. Surprisingly there is no significant difference in responses from Coalition and Labor supporters.