Pandemic politics

Australia

There is a lull in pandemic politics. Booster shots are on their way, and it is fairly certain that there will soon be approval for vaccination for children aged 5 to 11. That means 96 percent of our population would be eligible for vaccination.

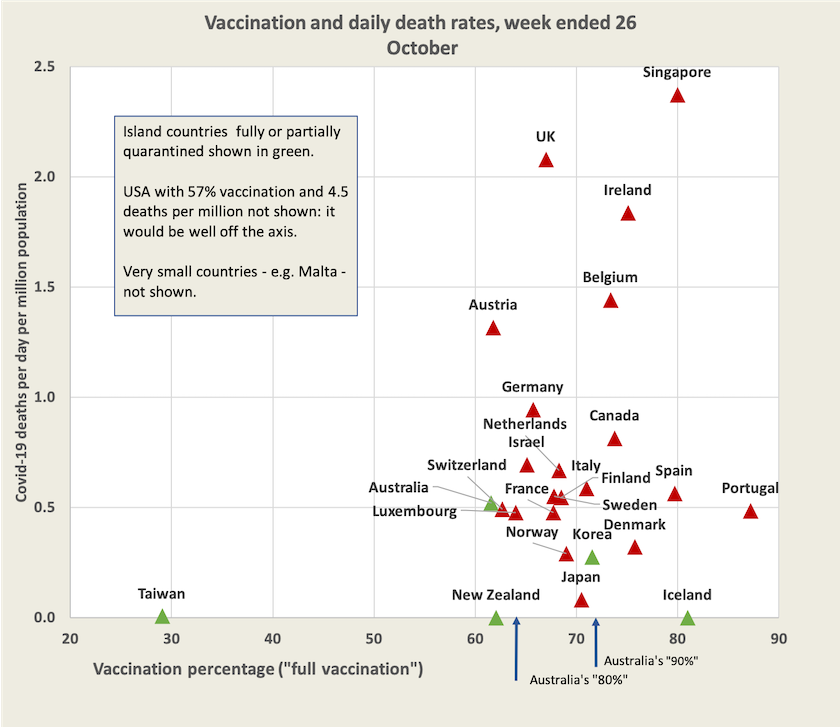

Perhaps, when that time comes, politicians and journalists will start to talk about real vaccination rates rather than about percentages of the 16+ population. The hype is about our becoming the most vaccinated country in the world, but the reality is that nationally we are only about 62 percent vaccinated (38 percent unvaccinated). That’s a full vaccination figure: with 73 who percent have received their first dose and will presumably go on to be fully vaccinated). Leaving aside the ACT, where 72 percent of the population is fully vaccinated and every imaginable biped over 12 seems to have had a first dose, our most vaccinated state is New South Wales, where 72 percent are fully vaccinated and 77 percent of the population has had a first dose.[1]

The scatter diagram below, an update of the regular chart, helps put these numbers into context. Assuming that we all reach at least a 77 percent level (the New South Wales first dose level ), that would place us where Ireland and Denmark are now (75 and 76 percent). But if we stopped at that level we would still be behind Singapore (presently dealing with an outbreak), Spain, Iceland and Portugal. On ABC Breakfast on Friday morning Flemming Konradsen of University of Copenhagen, commenting on Denmark’s rising cases and its need to re-impose some controls ,stressed that Denmark still has to get its vaccination rate higher. A quick inspection of vaccination progress in New South Wales suggests that vaccination is now proceeding very slowly: more effort will be required to reach and convince the still-unvaccinated.

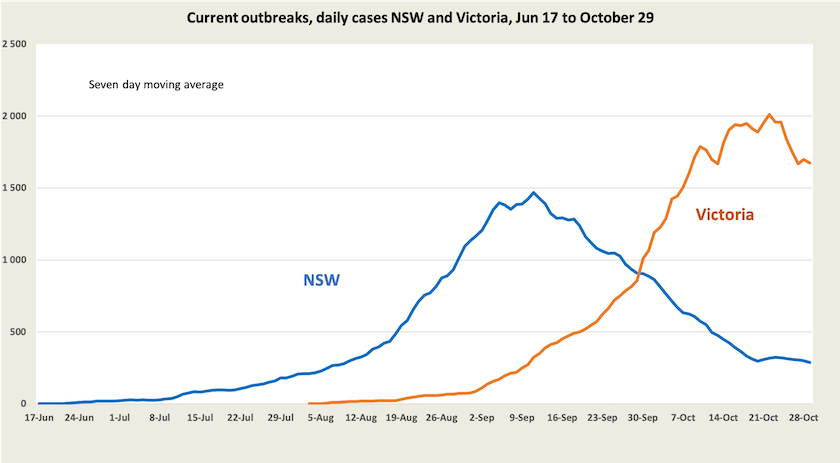

The virus is still spreading strongly in Victoria, while it seems to be stabilising in New South Wales at a significantly lower level (particularly regarding the fact that Victoria’s population is 20 percent smaller than New South Wales’).

Behind these gross figures there are significant regional differences. In New South Wales most new cases now seem to be occurring outside Sydney, and are spreading disproportionately among indigenous communities.

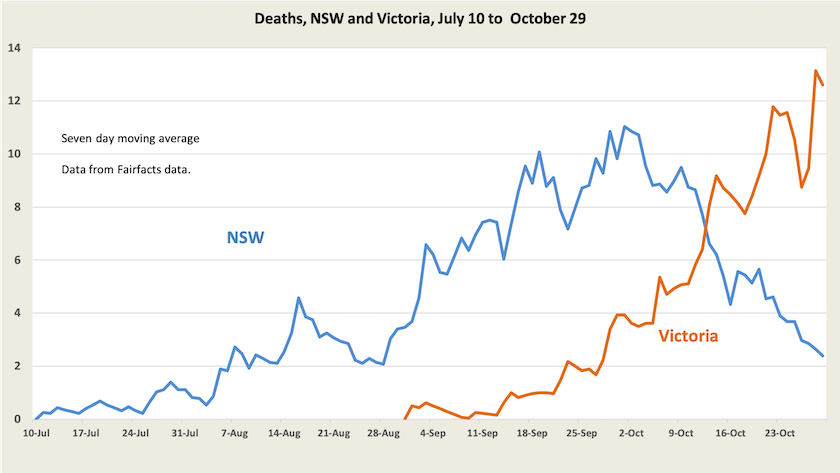

Thanks to Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues, there is data on daily deaths for these two states, shown below. Because deaths correlate fairly closely with hospitalisation (but with a lag), they are a reasonably good indicator of the demand on health services.

Deaths in New South Wales peaked on October 1, three weeks after cases peaked. That suggests deaths in Victoria should start to fall fairly soon, cases having peaked on October 14, assuming Victoria follows the same pattern as New South Wales. But if the virus is spreading with a lag in non-metropolitan regions, the load on country and provincial city hospitals may be yet to peak in both states. More importantly, in view of the three-week lag between infection and deaths, it should be noted that New South Wales had a substantial relaxation of restrictions just two weeks ago: its downward trend may not last.

Policymakers in other states would be looking at the New South Wales and Victorian situations, wondering how their states will fare when they open up, either on their stated dates and vaccination level targets, or when some careless or irresponsible visitor starts to spread the virus. Writing in The Saturday Paper Rick Morton discusses scenarios, based on Doherty models, of how the virus will spread in other states. No one can predict how the transition from elimination to endemicity will occur, but the Victorian experience does seem to confirm the Doherty modelling that vaccination has a tougher task to achieve if states open up when the virus is circulating at high levels.

Politically we can expect the Commonwealth to heap praise on the governments of South Wales and Tasmania, and to focus on every fault in Queensland and Western Australia as they all go about the same difficult task of trying to ensure that their already-stretched hospital systems are not overwhelmed

1 These figures are based on records of 16+ vaccination levels, multiplied by 0.8 to express them as a proportion of the whole population, and adding 2 percent to full vaccination levels and 3 percent to partial vaccination levels to account for the 5 percent of the population between 12 and 15, who are around 40 percent fully vaccinated and 65 percent partially. It’s a bloody nuisance trying to get sense from official figures produced by a government whose default modus operandi is secrecy.↩a

The rest of the world

Worldwide, vaccination progress is slow. Half the world’s population is still to receive a first dose, and only 38 percent of people are fully vaccinated – hardly a change from last week.

According to WHO data, cases and deaths are once again rising, mainly in Europe and Asia, while they are generally falling elsewhere (but data from Africa is very poor). Within Europe cases and deaths are rising most strongly in eastern Europe and Russia. In Asia cases are falling, but deaths are still rising in India.

Another finding from the WHO is that the case fatality rate is continuing to fall for all age groups. It is now only 5 percent for those over 65.

A significant letdown for the world’s poor has been the disappointing performance of Covax, the program intended to provide vaccines to every country, financed by richer countries. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism has an article How Covax failed on its promise to vaccinate the world, describing why it has so far delivered only 330 million doses. Some problems have to do with insufficient engagement between governments of donor and recipient countries. Some have to do with administrative snafus – how did a shipment of vaccines get delivered without syringes? Some have to do with delays in transferring intellectual property. But most of all the problem lies in the policies of richer countries that prioritise their own citizens’ immediate safety and that are stingy on helping the rest of the world, even though for many reasons everyone, rich and poor, can enjoy a safer and more prosperous life in a vaccinated world.

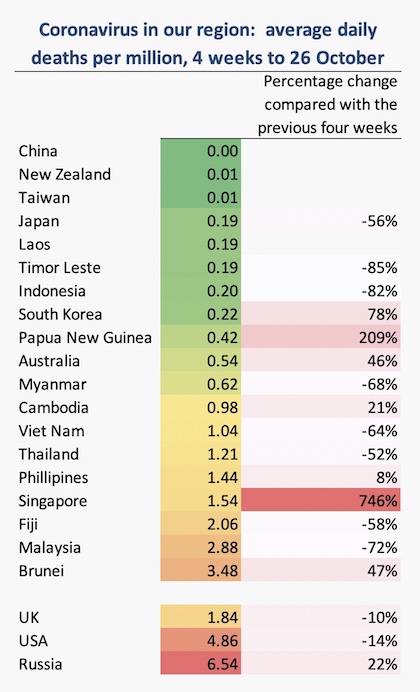

I have been asked to update earlier data on what is happening in our region. Data on cases is becoming less and less reliable for all countries as asymptomatic cases spread, and in most poorer countries there is only a low level of testing. Even data on deaths is somewhat scrappy, but it is possibly the best available and I have used it to construct the table alongside. Data for Cambodia and Myanmar may not be reliable and I have included data on UK, USA and Russia for comparison.

Singapore’s surge in cases and deaths is puzzling authorities, particularly in light of its high level of vaccination.

The other country with a surge in deaths is Papua New Guinea, a country with hardly any vaccination (1.2 percent), and where the virus is now spreading into remote provinces. At least 15 percent of those few people who are tested are testing positive. On last week’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed Jonathan Pryke from the Lowy Institute and Natalie Whiting, an ABC PNG correspondent, who explain a raft of reasons for this alarming situation – poverty, an underdeveloped health system, an unfriendly geography, superstition, a lack of awareness, other priorities in a country grappling with other diseases. Australia can and should lend a hand. PNG and the Delta strain. (12 minutes)

A perspective from a country doing very well is provided in an account of daily life in Portugal. People are still wearing masks inside, people are still maintaining a degree of social distancing, and people are still well aware of the presence of Covid-19.

Data sources

See the separate web page of hyperlinks to generally reliable information and analysis about Covid-19, including data on vaccination and the WHO Covid-19 epidemiological updates.