Pandemic politics

Australia's position in the vaccination race

Political hype about opening up rests on those “70 percent” and “80 percent” vaccination targets. In fact the more accurate description of those targets should be 56 percent and 64 percent, because they relate only to the population of those 16 and older, and they’re state averages, glossing over significant regional differences.

So in a few days when New South Wales goes through a further stage of opening up at its “80 per cent” target, 36 per cent of the state’s population, or 3 million people, will still be unvaccinated. Although many of the “freedoms” apply only to the vaccinated, it is impossible to segregate the vaccinated from the unvaccinated. Compliance with rules is well short of 100 per cent, and fully vaccinated adults and unvaccinated children can be asymptomatic carriers of Covid-19.

The AMA has added its voice urging caution on the New South Wales and other state governments. In a major report Public hospitals: Cycle of crisis it warns that public hospitals around Australia, even without having to deal with Covid-19, are already heavily stressed. If public hospitals have to deal with a rapid relaxation of public health and safety measures the situation will worsen. In the best case scenario, demand on ICUs will increase by 7 percent in December, while in the worst case scenario it could increase by 48 percent, peaking in January but staying high for many months.

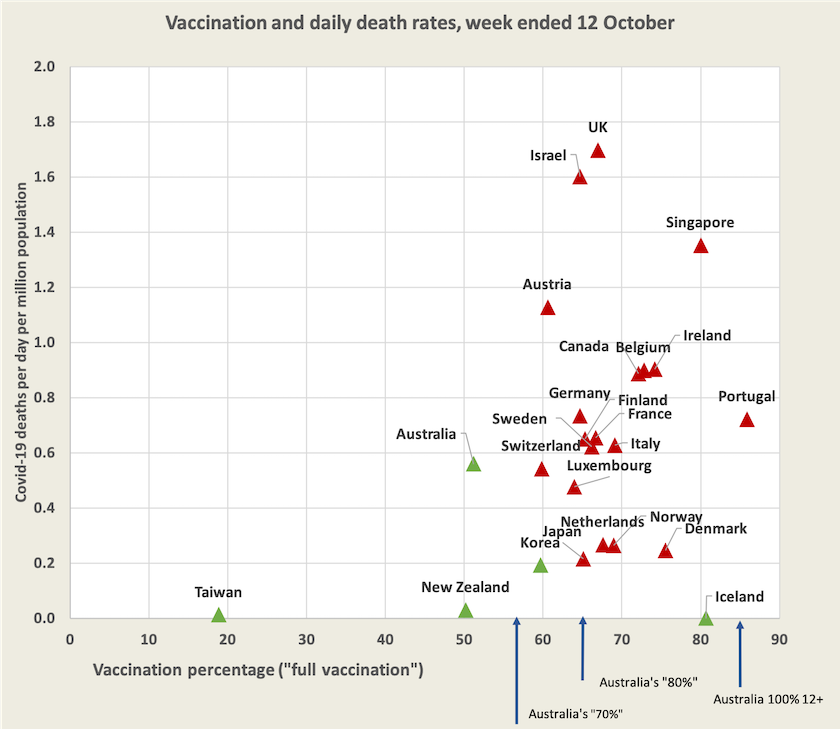

In comparison with other prosperous countries, although we are making good pace, we still have a long way to go with vaccination. The graph below is an update of the regular scatter diagram of vaccination levels and deaths in high-income countries which have achieved high vaccination rates, or which have kept the virus at bay with isolation (Australia, Taiwan etc in the green markers). Also shown along the x axis are three target points for Australia – the 56 and 64 percent vaccination levels (70 and 80 percent in government spin) and a theoretical ceiling of 85 percent if the whole 12+ population is vaccinated.

The good news is that those European countries that removed most restrictions a few weeks ago have not experienced a surge in deaths. Even in the UK, one of western Europe’s worst performers, the death rate is coming down.

Singapore has experienced an increase in deaths but when one examines the data from its Ministry of Health the virus is certainly not out of control. You can see Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong explain the Singaporean situation in a way that seems to be beyond the capabilities of our prime minister.

The US is still off the scale with 4.7 daily deaths per million, and vaccination stuck at around 55 percent.

Australia’s point on the above chart, at around 0.5 daily deaths per million population, is somewhat misleading because our 99 deaths last week were in only three jurisdictions where the virus is spreading. If New South Wales, the ACT and Victoria were considered as a “country” its daily death rate per million would be about 0.9 – around the same as Ireland and Belgium. And that’s in a period with a high level of restrictions in place. The cautious conclusion is that if our health care systems are not to be overwhelmed it would be rash for the Victorian and ACT governments to proceed too quickly with “opening up”.

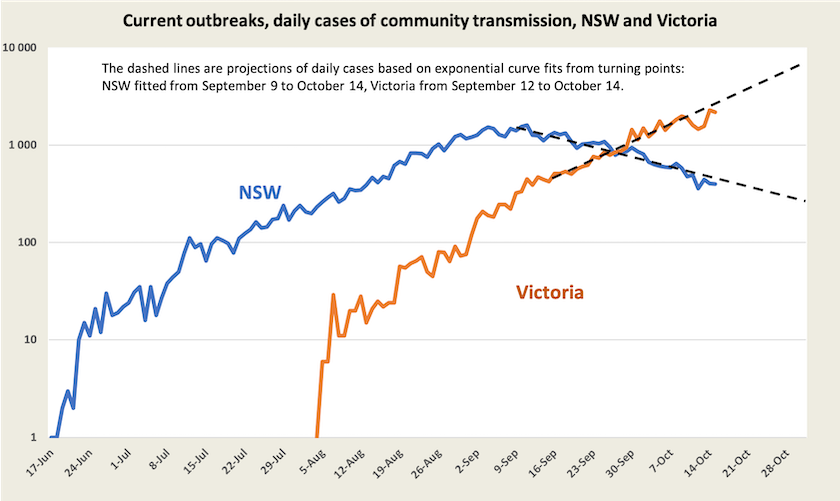

The graph below shows recorded cases in New South Wales and Victoria up to yesterday, October 15. (The ACT is not shown: its infections are bouncing around at around 30 to 50 cases a day with no sign of a trend – quite high for a population of 0.4 million.)

The dotted line for New South Wales is a projection of the downward trend since cases peaked in early September. The effect of the state government’s haste in lifting restrictions will be evident in the extent to which cases rise above this line.

In relation to New South Wales it should be noted that the situation in Sydney seems to be significantly better than in the rest of New South Wales. Such regional differences almost certainly relate to different vaccination levels. Even within Sydney there are big differences in vaccination rates: for example the densely-settled suburbs south of the city have quite low levels of vaccination. Australia’s experience with vaccination as aproblem with a strong regional component may at last force journalists and policymakers to abandon their lazy and meaningless classification of anything outside our capital cities as “regional”, as if our living places can be neatly classified into two homogenous blobs, and start thinking of regions seriously, including the distinct regions in our big cities.

After hasty suggestions that Victoria had hit its peak, there is no sign of a downturn as yet. It’s still on a trend of 5 percent daily growth, doubling every two weeks, shown on its dotted line. If the trend continues daily cases would hit 10 000 in early November. Victoria’s vaccination level is 50 per cent and in spite of a fast uptake – each day sees another 1 percent of its population vaccinated – vaccination isn’t keeping up with the virus. By comparison the infection rate in New South Wales peaked a month ago, when its vaccination level was only 36 per cent. There is something other than vaccination responsible for the different experiences of these two states.

In terms of public policy, case numbers, however, are less important than the stress on health systems and the distress of deaths. In both states the probability that a case will require hospitalisation is falling. Vaccination is the most compelling explanation for this fall, but early intervention and better treatment would also be playing their part. Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues have done us the service of including data on hospitalisation, ICU admissions, and deaths by vaccination status, as a link on their daily updates – so far only for New South Wales. These are the variables that indicate the load on our health system. It won’t be long before case numbers start to lose significance, because more and more infections will be asymptomatic, and their inclusion in records will depend on states’ differing approaches to testing. Importantly, public health experts believe that the rates of hospitalisation are at the lower end of the models’ range of predictions, even though there seems to be lower compliance than assumed in the models.

As for the other jurisdictions, apart from Tasmania (53 percent vaccinated), they are all lagging at around 44 percent vaccination level, although their rates of vaccination vary: see the ABC’s vaccination site for estimates of when they will reach those “70 and 80 percent” targets. They are coming under increasing pressure from so-called business lobbies to provide a timetable for opening up – a pressure that’s applied far more to the Labor governments of Queensland and Western Australia than to the Liberal governments of South Australia and Tasmania. Their defences will break at some stage, but they don’t know when: one careless person could set off an outbreak. The only way these states could provide the semblance of a firm timetable would be to deliberately allow the virus to spread before their populations are well vaccinated. Is that what the lobbies want these governments to do? Norman Swan’s Coronacast has a session dedicated to the situation in these jurisdictions.

For a concise cover of vaccination progress in Australia, with state and age disaggregation, the ABC’s Casey Briggs has a 6-minute presentation. If we can maintain momentum and reach the vaccination levels of our best regions, we could well become one of the world’s most vaccinated countries.

Anti-vax terrorism

The Burnet Institute reports (with a link) on a survey of Australia scientists, revealing that one in five have been subject to death threats or threats of physical or sexual violence after speaking to the media about Covid-19. It also reports (with a link) on an international survey published in Nature, revealing similar levels of intimidation in other countries. Scientists are subject to attack when they give factual data about the low levels of risk associated with vaccination and when they point out the uselessness of supposed cures and prevention measures.

On Thursday morning’s ABC Breakfast program Fran Kelly interviewed Margaret Hellard of the Burnet Institute and Lyndal Byford, of the Australian Science Media Centre – COVID-19 experts cop abuse and death threats– about these surveys. They point out that social media, with its cover of anonymity, is a common channel for abuse. (12 minutes)

It’s not only scientists attracting abuse: workers and employers enforcing rules about masks or requesting evidence of vaccination are subject to intimidation. Deutsche Welle has a 12-minute video on anti-vax movements and their intimidating behaviour. (The video includes plenty of clips from Australia.) The issue is not so much about the specific issue of vaccination. Rather it’s about a bunch of discontented people seeking a cause around which to mobilise politically. Behavioural experts on the panel point out that those who rely heavily on social media are more likely to hold to conspiracy theories than those who rely on established news outlets.

Social media certainly present a problem, but are we making it take a disproportionate share of the blame for the proliferation of conspiracy theories and people’s attraction to fake news? Governments, particularly those on the “right”, that have abandoned principles in favour of populism, that have dumbed-down education curriculums, and that have dismissed evidence-based policy proposals with ridicule, bear much of the blame for our gullibility.

Vaccinate the world

As we in Australia and other “developed” countries head towards a high rate of vaccination, and are already in the early stages of arranging booster shots, only 5 of the world’s 28 poorest countries have reached single-dose vaccination levels of 10 percent of the population. In Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, South Sudan and Tanzania, single-dose vaccination rates are below 1 percent.

This is one of the revelations in a report released last Monday – Shot of hope: Australia’s role in vaccinating the world against Covid-19 – produced by the End Covid for all coalition. Their goal is to achieve 30 percent vaccination by the end of this year for low and middle-income countries, and global vaccination coverage by the end of next year. They call for Australia to make a fair contribution to COVAX, a program dedicated to obtaining fair and equitable access to vaccines in every country in the world: so far our contribution has been low in comparison with most high-income countries.

The urgency is not only about equity: it’s also about heading off the possibility of even worse mutations developing.

On Monday’s ABC Breakfast – Developing countries face 10-year wait to fully vaccinate their citizens – Tim Costello summarised the report. The task looks enormous, but he reminded us of the similar challenge, and the successes, in combatting AIDS.

Data sources

See the separate web page of hyperlinks to generally reliable information and analysis about Covid-19, including data on vaccination and the WHO Covid-19 epidemiological updates.